Wool and Colonialism

It’s often said that Australia was built by “riding on the sheep’s back”, and that’s partially true. Many settlers in Australia became rich by claiming and clearing land to farm sheep, and the foundations of much of the society that we know today were built on that wealth.

But that adage needs some tweaking: white Australia rode on the sheep’s back, and those sheep grazed on land stolen from Indigenous people and wildlife.

Stolen Land

Most of what previous generations of Australians learned in school about the country’s Indigenous population describes a nomadic people with no claim to the land, according to the white settlers who called it terra nullius – land belonging to no one.

“The kangaroo is my family totem. … They are my culture and my family’s spiritual connection to country.”

The land has never been ceded by Australia’s First Peoples, and no treaty has ever been signed.

While Aboriginal people did hunt and gather food, they also had sophisticated farming and agricultural techniques, including planting root vegetables, grains, grasses, and fruits; building dams, trenches, and wells to water crops; and using fire to generate grass growth. They had houses and villages constructed in various styles, depending on the climate.

These truths cast colonisation in a harsher light. It’s much easier to sympathise with the commonly portrayed stereotype of English outcasts – the Aussie “battlers” trying to eke out an existence in a harsh, unfamiliar, and “empty” land – than it is to reckon with the reality that a privileged group systematically cleared and conquered areas that were already inhabited and intentionally managed.

Of course, the blame doesn’t fall squarely on one industry, but it’s worth noting that the majority of the land was (and still is) used to graze sheep and cows.

Around 56% of Australia’s total land area is currently used for livestock grazing. By comparison, broadacre cropping takes up 3.5%, horticulture less than 0.1%, and urban areas 0.2%. Only 7% is set aside for nature conservation, and 13% is protected for use by Indigenous Australians.

The land has never been ceded by Australia’s First Peoples, and no treaty has ever been signed.

Overstocking

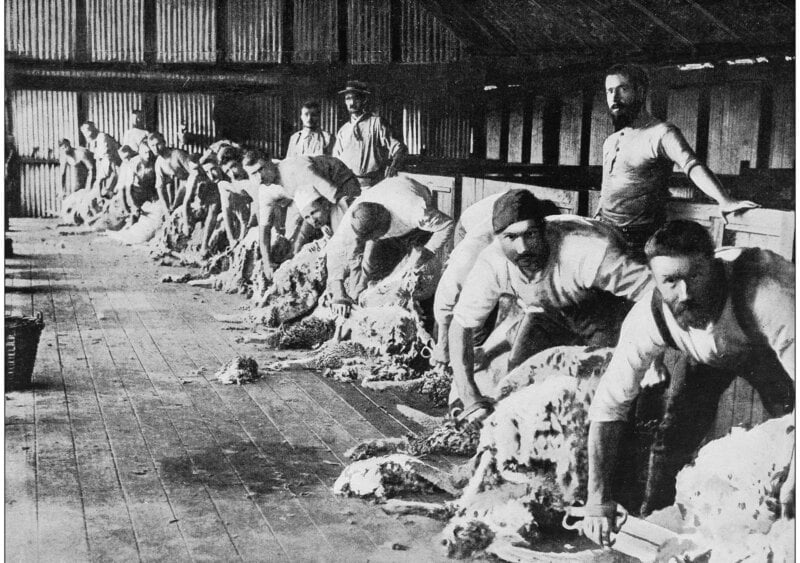

Captain John Macarthur was one of the first Englishmen to be “granted” land and stock as well as unrestricted convict labour to establish his farm. By 1801, he was the largest sheep owner in Australia, and in 1804, he set about establishing his own merino stud farm with another “grant” of 5,000 acres and 30 more convicts. Macarthur may have been one of the first, but the same story played out with many more white settlers over millions more acres.

Often celebrated as one of the founding fathers of Melbourne, John Batman sailed from Tasmania around Port Phillip in 1835 and found rich grasslands. He “negotiated” a treaty with the local people, offering blankets and axes in exchange for 500,000 acres of land. Soon, 20,000 sheep were brought across the Tasman Sea, and by 1839, almost 1 million were encamped in the area.

As the sheep multiplied, the environment began to change. Fifth-generation sheep farmer and now regenerative-farming advocate Charles Massy notes in his book Call of the Reed Warbler that “sheep ate the heart out of the country and its vast swathes of diverse, long-adapted natural grasslands”.

Graziers were so keen to cash in on the burgeoning wool industry that they put more sheep on the land than could be sustained and continued to move into drier, more marginal areas. At the wool industry’s peak in 1980, there were 173 million sheep in Australia. Their omnipresence devastated the environment and displaced people and wildlife.

© We Animals

© We AnimalsDispossession and Slaughter

The creation of private property made it difficult for communities of First Peoples to hunt, access water sources, and manage the land as they once had. Aboriginal peoples hold their relationship with the land and animals as fundamental to their identity and spirituality, so the destructive nature of colonisation bore a terrible psychological impact.

Dispossessed of the land that had nourished them for so long, Aboriginal people became dependent on white society to try to survive – but many didn’t.

Anthropologist and Anglican clergyman AP Elkin noted in 1951 how this process evolved:

When cultivation is associated with grazing cattle and sheep … ever increasing in numbers, the settlers required all the grass and must not be disturbed by hunts-men’s activities. So the native fauna must go, including the Aborigines, unless they change their ways of living.

There was no respect for Aboriginal life at all, let alone the Aboriginal way of life.

Extermination of Everything Natural

Wild-animal populations retreated or disappeared as land clearing encroached on their homes and food sources.

Kangaroos were rounded up and massacred – as they still are today – and blamed for the lack of grass on paddocks that were often overstocked with sheep and cows. Dingos and birds of prey, too, were hunted in order to keep them out of the sheep paddocks.

No animal was safe. According to the Australian Koala Foundation, 8 million koalas were hunted and killed for their fur until the late 1920s. The Queensland state government alone sold licenses to 10,000 hunters for “open season” in 1927 in response to reports of “uncontrollable” koala populations and in an attempt to boost rural employment.

In Australia, 34 mammals have become extinct since European colonisation began, and more than 1,700 others are now threatened or endangered. No other country has seen so many mammals become extinct. Koalas, once deemed an uncontrollable “pest” by settlers, are now on the brink of being listed as an endangered species.

In her 2021 book, Injustice, which examines the impact of colonisation in Australia, author Maria Taylor explains how the land came to be dominated by exotic species:

From the perspective of Australian wildlife, with the settlers that came in waves after 1788 the original life-sustaining habitat was rapidly “owned”: cleared, silted over and eaten out by hard-hooved exotic animals, often overstocked, or it was ploughed up and planted.

Colonialist Legacy in the 21st Century

The ethos of clearing and killing anything native for the sake of economic progress remains deeply ingrained in the dominant agricultural – and even political – mindset of Australians.

Despite being on the Australian coat of arms and a sacred totem animal for First Nations people such as the Palawa, kangaroos continue to be persecuted as perceived competition to livestock for grazing pastures. Millions are savagely killed by commercial and recreational hunters each year because they’re considered “pests”, even though sheep and cows are the unnaturally introduced and overpopulated species.

Australia still largely has an agricultural-export economy, meaning that these industries have a huge influence over political decision-making. Farmers topped the list of lobbyists who were granted ministerial meetings in New South Wales from 2014 to 2018, with almost 100 meeting days counted. Even today, the industries that played a fundamental role in Australia’s dark history continue to operate largely unquestioned.

Australia has the worst deforestation rates of any developed nation, driven by pasture for animal agriculture, and the kangaroo-shooting industry represents the largest slaughter of land-dwelling wildlife in the world.

How Do We Do Better?

© Unsplash/Johan Mouchet

© Unsplash/Johan MouchetIt’s impossible to dismantle all the colonial influence of the last 200 years, and as a modern society, we still need to farm the land in order to produce food and fibres. But how can we use this information to move forward?

Indigenous educator and writer Aunty Ro Mudyin Godwin has been campaigning to end the kangaroo slaughter in Australia – what she sees as an essential step towards reconciling the damage done to her people. She told a recent government inquiry about the cultural significance of kangaroos:

“The kangaroo is my family totem. … They are my culture and my family’s spiritual connection to country. Every time one of these totemic animals is gunned down a part of myself – my family – dies. Our cultural connections die. The interconnectedness of country dies, our creative spirit torn apart. Indeed, I wonder if that is seen as a treasured bonus in the eyes of the colonial killer. To see the very government that governs this stolen land under the coat of arms, the kangaroo and the emu, profit from the commercial slaughter of kangaroos like some sort of trophy exemplifies blatant and obnoxious colonialism.”

Australia needs more Indigenous peoples’ involvement in land management and government incentives in order to regenerate the land. This means reducing our agricultural footprint by focusing on sustainable cropping and protecting native animals.

Such changes take time, especially when the government is involved, but it’s within each individual’s reach to sway the market with the power of their dollar. When interviewed by author Maria Taylor for Injustice, Bwgcolman elder and renowned artist Billy Doolan said:

“There is hope if people make changes to heal the land and live with the native species. Mother Earth can heal herself if we help. Don’t overharvest, overfish, let them live, eat something else.”